Cancer doesn’t gender-discriminate

Unfortunately, society does

27 Jan 2024; as published on www.dhakatribune.com

Every year, over 5,000 Bangladeshi women die from cervical cancer. And yet, this cancer is one of most easily preventable and treatable cancers. Not only that, the treatment is very affordable. So how can this be?

It seems it is as much an issue of gender inequality as it is about medicine. Let's look at why: Cervical cancer is primarily caused by infection from specific genotypes of the Human papillomavirus (HPV). There are two ways to address it. The first is to prevent it from occurring in the first place, by vaccinating girls and boys with the HPV vaccine before sexual initiation. The second is to prevent pre-cancers from evolving into cancers through early detection and treatment.

In 2020, WHO released a global call to action to eliminate cervical cancer as a public health problem. It is centered around ensuring that 90% of the target population is vaccinated against HPV, 70% of the target group women are screened with a high-precision test, and 90% of pre-cancer and cancer cases are treated. This is not easy -- it will require dedication and commitment -- but it is fully possible.

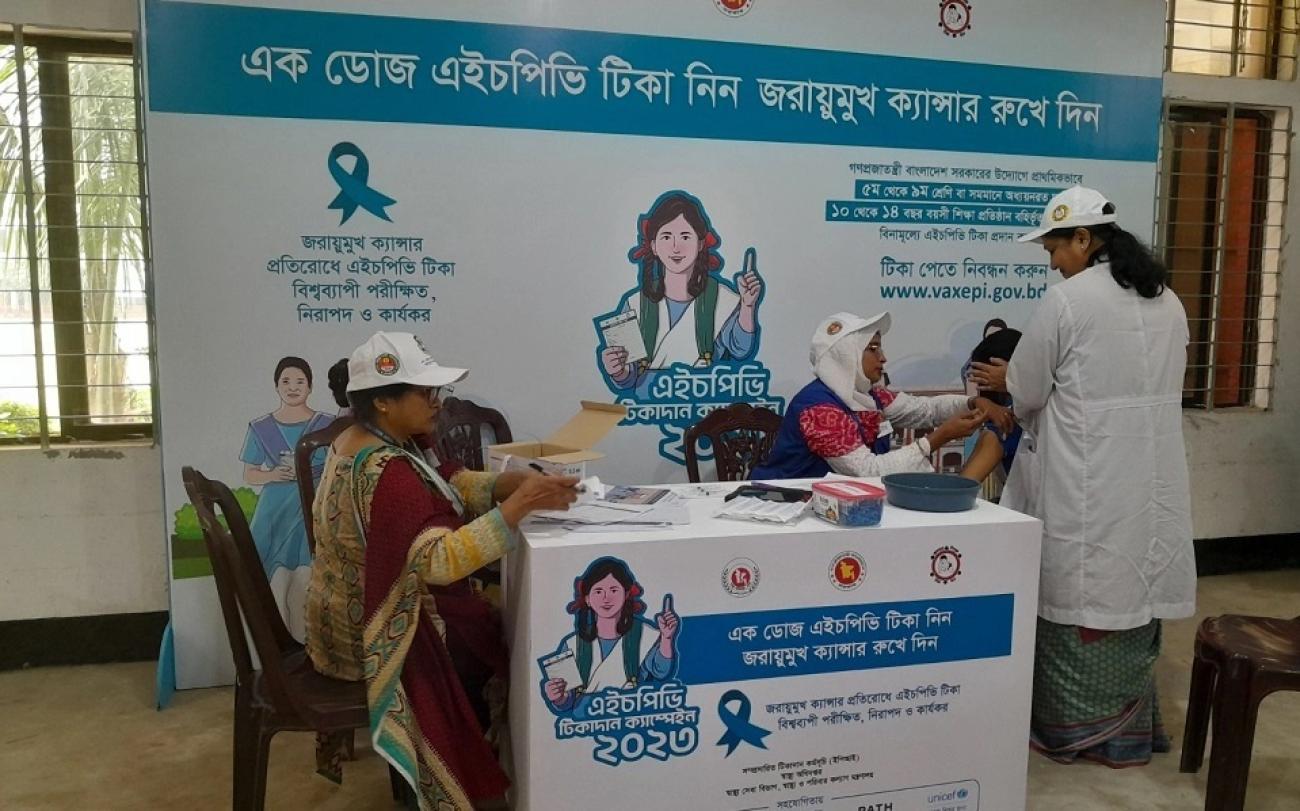

The government of Bangladesh has committed to achieving these goals by 2023, for which it should be commended. An HPV vaccination campaign was launched in October 2023, targeting all girls aged 10-14 years in the Dhaka division with the plan for phased divisional expansion; in the future, this single-dose vaccine will be integrated into routine vaccination for girls aged ten years.

A big part of the work ahead lies in supporting the health system adequately, but that will not be enough, because this is an area that is heavily influenced by social norms around gender equality and the role of women.

Early sexual initiation is a risk for HPV infection. A big proportion of the thousands of girls who had early marriages are experiencing various symptoms of cervical pre-cancer in their late 20s and 30s. In the context of rural, marginalized Bangladesh, we often see young women afflicted with the disease, most likely due to early marriage and possible HPV infection.

These same women, often rural, poor, and at risk of violence, may be crippled with dependency, both social and financial, that prevents them from seeking care. Layers of social and gender equity and power dynamics hence hold these women and girls in more ways than we may imagine.

Take the case of women who are positive in the screening test. Undergoing the very simple and effective treatment known as a thermal ablation means having to abstain from sexual activity for one month. When they hear this, many women say they must first discuss it with their husbands.

Some do, others are too afraid to broach the topic. In the end, a heartbreaking number of them never return to the health facility. They decide not to accept a life-saving treatment, even after dedicated health care providers follow up repeatedly.

Cervical cancer can be eliminated in Bangladesh, and it can be done in a short time. It will require support for the health system, predictable financing and a focus on vaccines, along with screening treatment and nationwide awareness. But our experience also tells us that we have massive work to be done on social and behavioral determinants of health –– engaging women and their partners and families.

If we get it right, it will pay dividends much beyond the health sector, not least through the contributions of healthy and empowered women and girls.